Reviewed

for Anglicans Online

by Terry Brown

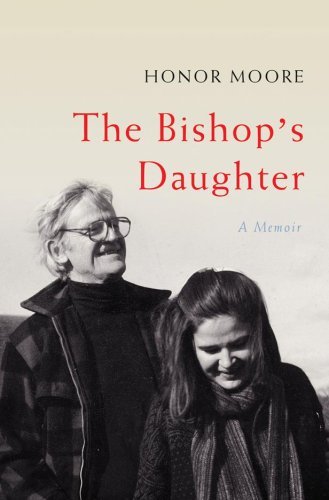

The Bishop's Daughter

By Honor Moore.

W. W. Norton, 2008. ISBN 0393059847. 352 pages, hardcover; paperback forthcoming in May 2009.

Honor Moore's The Bishop's Daughter is deserving of a reflective (and, I daresay, prayerful) reading. On the surface, it is a very personal memoir of her father, Paul Moore, Episcopal bishop of New York from 1972 to 1989. As first excerpted in The New Yorker a few months before its publication, it has become (perhaps not too strong a word) notorious for the disclosure of her father's active bisexuality. As such, her siblings publicly disowned the book and the current Episcopal bishop of New York felt called to comment upon it publicly on behalf of the church.

Honor Moore's The Bishop's Daughter is deserving of a reflective (and, I daresay, prayerful) reading. On the surface, it is a very personal memoir of her father, Paul Moore, Episcopal bishop of New York from 1972 to 1989. As first excerpted in The New Yorker a few months before its publication, it has become (perhaps not too strong a word) notorious for the disclosure of her father's active bisexuality. As such, her siblings publicly disowned the book and the current Episcopal bishop of New York felt called to comment upon it publicly on behalf of the church.

The book's intention is actually somewhat broader yet also narrower, reflected in the book's title: the bishop's daughter's attempt to understand her parents' marriage, thus also the family life of herself and her eight siblings, all related with the active Christian ministries of both her parents—and her own subsequent growth and development (not to mention confusion) as an adult, including ongoing conflicts and resolutions with both her parents before their deaths.

The genre is an increasingly common one, both from women and men, and it is an extraordinarily challenging one. In this respect, the book both succeeds and fails, though it never ceases to be of much interest in the stories it tells and the issues its raises, both directly and obliquely, indeed, even by its publication.

The book succeeds in its honesty—particularly, its portrayal of the advantages and disadvantages that her parents' great family wealth and sense of entitlement brought to their marriage, family life and ministries; its re-creation of part of the world of politically radical Anglo-Catholicism in the Episcopal Church in the fifties through the seventies, exemplified by an attempt to live the Catholic Worker spirituality of Dorothy Day in the slums of Jersey City and among the Episcopal elite of Indianapolis, culminating in active participation in the Civil Rights struggle and episcopal ministry in Washington DC and New York; and, of course, the fragility of her parents' marriage (and, indeed, both the bishop's marriages) related with the bishop's sexuality and his very ambivalent attitude towards it. It is better to have these events narrated by someone directly involved rather than hearsay and gossip by outsiders.

But such a book carries great risks. The Bishop's Daughter has not been able to avoid these entirely and in some respects the book fails. The combination of biography (the bishop's) and autobiography (the author's) is often not a seamless one. The author's honesty about the travails of her own life (sometimes blamed on her parents, sometimes not) is commendable but sometimes clogs the narration. In lieu of a father from whom she is sometimes alienated later in life, her therapist takes on an anchoring role. As such, echoing his reflections, sometimes the book feels more like a case study in its emphasis on excessive detail than a work of art in which omission and economy are essential.

Despite these reservations, the book is worth reading for the many issues it raises, directly and indirectly: the relation between the public and the private, especially for bishops, and the relative valuing of these two spheres in relation to public disclosure; the failure of commonly held dimorphic views of gender as strictly "male" and "female" in polarity, over against genuine experience which is often very ambiguous, if we are really honest (as the author is, both about her father and herself); the tremendous burdens placed upon clergy families, including episcopal families; generational differences in living with and living out homosexual desire, including its relation to marriage; changing understandings of boundaries; and, perhaps most importantly, the role of Christian faith (or lack of it) in living as broken people in a broken world today.

Is the book harmful? Did Honor Moore do a great disservice to her family and the church in writing and publishing it? Though the book is at times confused, maddening and excessive in its detail, I think not. North American and European culture, because of cultural changes going back at least a century, now expects to see not just the front of the beautiful (or not so beautiful) tapestry but also the messy backside that gives the front its strength. The danger, of course, is becoming so obsessed with the backside that one ceases to care about the front; or even hanging the tapestry backwards, claiming that the back is the front. (Here a proper biography of Paul Moore is needed, assessing better his public and private ministry that, in the end, filled the cathedral in New York with mourners at his funeral.) The author has woven a tapestry about her parents, showing us both sides. And in the end little is lost and much is gained. The work is well worth reading, but only if done in a broad spirit of prayerful understanding, not condemnation.

For those who have already totally written off the Episcopal Church USA for its immorality and compromise with these evil times, this book, if read with only sex on the mind, will probably only reinforce that view. Yet Paul Moore was many times on the side of good despite his troubled personal life. This book does not lose that insight but sometimes obscures it. One welcomes the bishop's daughter's search for the faith of Christ's suffering and resurrection that sustained her parents through much difficulty.

|

The Right Reverend Dr. Terry Brown is retired Bishop of Malaita, Church of the Province of Melanesia. |