A

review for Anglicans Online

by Richard Mammana

A review of

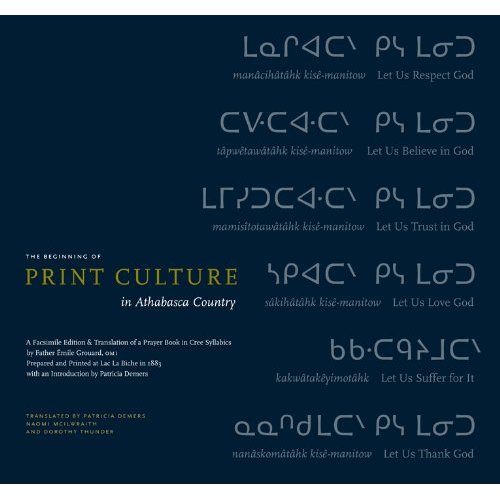

The Beginning of Print Culture in Athabasca Country: A Facsimile Edition and Translation of a Prayer Book in Cree Syllabics by Father Émile Grouard OMI, Prepared and printed at Lac La Biche in 1883.

Foreword by Arok Wolvengrey; Introduction by Patricia Demers; translated by Patricia Demers, Naomi McIlwraith, and Dorothy Thunder. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2010. Pp. xxviii, 457; hardcover, $100.00.

The French-born Roman Catholic missionary priest Émile-Jean-Baptiste-Marie Grouard (1840-1931) arrived in Québec in 1860 as a member of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, a religious order distinguished for its extensive missionary activities among indigenous peoples in northern and western Canada. Following ordination, he served a group of missions at Fort Chipewyan, Fort Providence and Fort Liard in what are now Alberta and the Northwest Territories for 13 years, after which he spent a medical furlough of two years at home in France. His arrival at Lac La Biche in 1876 marks the beginning of the important linguistic, cultural, religious and bibliographic moment delineated in rich detail by this critical edition of one of Grouard’s major liturgical publications.

The French-born Roman Catholic missionary priest Émile-Jean-Baptiste-Marie Grouard (1840-1931) arrived in Québec in 1860 as a member of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, a religious order distinguished for its extensive missionary activities among indigenous peoples in northern and western Canada. Following ordination, he served a group of missions at Fort Chipewyan, Fort Providence and Fort Liard in what are now Alberta and the Northwest Territories for 13 years, after which he spent a medical furlough of two years at home in France. His arrival at Lac La Biche in 1876 marks the beginning of the important linguistic, cultural, religious and bibliographic moment delineated in rich detail by this critical edition of one of Grouard’s major liturgical publications.

In the course of a long missionary career that included his consecration as bishop in 1891, Grouard produced liturgical publications in Montagnais (1877 and 1878), Loucheux/Gwich’in (1879), Beaver (1888) and the major 1883 text in Cree that forms the core of this volume. Unlike many contemporary missionary publications, Grouard’s 1883 translation and publication of Kâtolik ayamihêwi-masinahikan (literally Catholic Prayer Book) was printed at the mission of Notre Dame des Victoires at Lac La Biche on a small, Paris-manufactured press. (The more usual production process involved the time-consuming shipment of manuscripts across the Atlantic to European publishers, who set type with or without knowledge of indigenous languages, and subsequent return by boat.) Grouard’s local efforts make Kâtolik ayamihêwi-masinahikan the first book to have been written and published in Athabasca country without the need for transatlantic assistance.

This facsimile edition is taken from a copy of the original 224-page Kâtolik ayamihêwi-masinahikan at the Provincial Archives of Alberta in Edmonton. It includes a scan and enlargement of each page with its Cree Syllabic text, a translation into English, and two further representations of the Cree: a transcription of the syllabics into Roman letters, and a transliteration of the Cree using Standard Roman Orthography informed by modern linguistics.

Supporting documentation includes an introductory essay with a thorough portrait of Grouard himself, and of his important roles in the large Athabasca-Mackenzie vicariate as “priest, missionary, navigator, geographer, explorer, builder of towns, architect, painter, writer, printer, and agriculturalist” (xxi). One of the most fascinating dimensions of the book is its depiction of Lac La Biche as a polyglot community in which Cree-, Chipewyan-, Montagnais-, and Beaver/Tsattine-speakers lived and worked side by side with French nuns and missionary priests as well as Hudson’s Bay Company traders of Scots-English background. In light of subsequent missionary policies that did much to impoverish the linguistic heritage of First Nations peoples, it is highly significant that Grouard chose to place a priority on indigenous language publications. Through his work, we see a Lac La Biche in which commerce is conducted in English; worship and education take place in Latin, French, and several indigenous languages; and conversations among and within groups must have taken place in whatever language was held in common by the speakers. The authors note thoughtfully in light of these linguistic realities that “it seems to us important not to belittle or demonize the missionary, but to try to enter his mind. If we attend to its nuance, his text becomes an almost-speaking document, in which, curiously, we can hear both the speaker and his audience” (xii).

The afterword by Patricia Demers, Naomi McIlwraith and Dorothy Thunder is entitled “Language and Devotion: A Missionary’s Use of Cree Syllabics.” In their careful and thorough examination of linguistic dimensions of the text, they note correctly that “there is no comparable examination and reconstructive translation of a mission press imprint in the language of the people being catechized” (445). In this sense, the work is a watershed event in First Nations linguistics and mission studies in general. Demers, McIlwraith and Thunder write that they are “more and more impressed by [Grouard’s] agility and deep understanding” of Cree as shown in his “adaptability” and “his knack for fashioning Cree Syllabics to convey biblical discourse” (453). One memorable re-translation of an account of the Catholic doctrine of Jesus’ incarnation “leaves us with the fanciful but fitting image of Jesus tobogganing down a great hill to earth.”

Without in any way detracting from the significance of the 1883 publication of this work, it is important to note that a very large body of published material in Cree Syllabics already existed by this date in liturgical, scriptural, hymnographic and poetic publications begun some four decades earlier by Wesleyan and Church of England missionaries at Moose Factory, Ontario. It is a significant understatement to say that “some mission publications (Catholic, Anglican, and Wesleyan) predated Grouard’s efforts” (x). There is also little situation of Grouard’s Prayer Book in the context of the substantial body of contemporary Roman Catholic translations into First Nations languages by missionary linguists such as Frédéric Baraga (1797-1868), Jean Baptiste Thibault (1810-1879), and Lucien Adam (1833-1918). Likewise, there is no careful situation of the Grouard text with other, later missionary imprints from Athabasca itself—such as material from the (Anglican) Church Missionary Society’s press at Athabasca Landing, or the prodigious output of material in local languages translated especially by William Carpenter Bompas (1834-1906), William West Kirkby (1827-1907) and Alfred Campbell Garrioch (1849-1934). One last criticism is that it is unclear whether there is or will be a digital dimension for the republication of this important work in addition to this attractive but expensive hardcover version. Many nineteenth-century missionary imprints have been digitized to high standards by online initiatives such as Early Canadiana Online/Canadiana.org, where they are offered for scholarly use at no cost.

These matters aside, The Beginning of Print Culture in Athabasca Country opens important new dimensions for study for modern scholars of mission, linguists, and Cree-language students. Historians of the Canadian Northwest are deeply indebted to these scholars and their Cree Elder collaborators for their work in preparing for a wide audience “a book of consequence that offers considerable clarification on the relationship between the missionary’s message and the medium through which he delivered that teaching” (454) while also taking into account the previously understudied mutual “influence of Native and missionary impulses” (xii).