A review for Anglicans Online

by Richard Mammana

A review of

Professional Indian: The American Odyssey of Eleazer Williams

By Michael Leroy Oberg, ISBN 9780812246766, University of Pennsylvania Press.

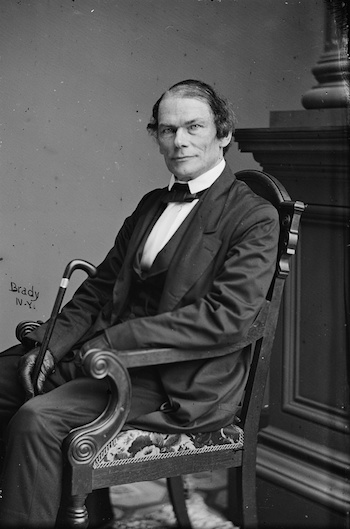

One of the most colorful figures in the history of the Episcopal Church in the nineteenth century—and the field of candidates is vast—rests in his second grave under a headstone in the cemetery adjacent to the Church of the Holy Apostles in Oneida, Wisconsin. His name is Eleazer Williams, and Michael Oberg’s recent biography is the first modern, scholarly treatment of a man who managed to conduct an impressive ministry and important national advocacy despite the considerable burdens of his own eccentricity.

One of the most colorful figures in the history of the Episcopal Church in the nineteenth century—and the field of candidates is vast—rests in his second grave under a headstone in the cemetery adjacent to the Church of the Holy Apostles in Oneida, Wisconsin. His name is Eleazer Williams, and Michael Oberg’s recent biography is the first modern, scholarly treatment of a man who managed to conduct an impressive ministry and important national advocacy despite the considerable burdens of his own eccentricity.

Eleazer Williams was born in Quebec in 1788 with the name Onwarenhiiaki, and grew up in the French Catholic Mohawk settlement of Kahnawake. His part-Mohawk father sent him in 1800, against his Catholic mother’s wishes, to Massachusetts to study for the Congregational ministry. After publishing a series of controversial tracts in English and Mohawk, and possible service as a spy and translator during the War of 1812, Williams became an Episcopalian in 1815. He prepared for ordination under John Henry Hobart, and was ordained to the diaconate in 1826 though never to the priesthood.

As a deacon, Williams determined to involve himself in the forefront of the young American republic’s policy toward Native Americans, positioning himself as a clergyman of mixed ancestry who could understand separate constituencies. He focused initially on his Iroquois kinfolk, the Oneida people of central upstate New York, participating in the process by which they were moved en masse westward to their major current tribal lands near Green Bay. He ministered among the Oneida in their Wisconsin settlements, translating part of the Book of Common Prayer into Mohawk for their use, and helping to establish a community that remains resolutely Anglican to this day. The Oneida themselves would reject Williams’ ministry by 1832, however, and by 1842 Jackson Kemper had forbidden him from ministering to Native Americans in his large northwestern jurisdiction.

From 1839 Williams began to claim that he was the Lost Dauphin, Louis XVII of France—the younger son of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. Williams alleged that he was spirited away by royalist sympathizers during the French Revolution and did not in fact die in prison as a ten year old in 1795. He insisted that his memories of early childhood in the French court had been suppressed by the trauma of the war and a transatlantic journey. His story was a sensation for magazines, newspapers and biographers around the world, as floods of European and American inquirers visited to verify his claims. Williams produced a dress with a twelve-foot-long train, supposed to have belonged to his late mother Marie Antoinette. At several points he contemplated abdicating his regnal rights to other claimants who requested his acquiescence to clarify their own pretenses. He greeted exiled survivors of the French Revolution as his long-lost friends and distant cousins—and they sometimes reciprocated by their own surprised recognition of someone they had known as children at Versailles.

Williams’ last ministerial posting was at the Mohawk reservation of St. Regis/Akwesasne on the New York-Ontario border, where he worked as a schoolmaster to prop up an unsuccessful anti-Catholic presence on the American side. Episcopal Church missionary societies supported Williams’ work here through his death in poverty in 1858, by which time his claims to the French throne were known around the world, and an otherwise-obscure rural deacon lived in terror of assassination by the enemies of his imagined parents and their regime.

Although he has faded into obscurity today, Williams was famous enough in his day to be satirized by Mark Twain in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. His translation of the Book of Common Prayer went into a second printing a decade after his death. A 1937 MGM feature film King without a Crown revived public interest yet again, and a wide variety of American newspapers covered the exhumation of Williams’ remains from New York in 1941, when he was reburied at Oneida.

Recent genetic tests on the heart of Louis XVII have proven that he did in fact die as a ten year-old during the French Revolution, meaning that Williams’ fanciful claims about his parentage and identity were false despite the sincerity of his recollection of lullabies on the lap of Marie Antoinette.

Oberg has done the investigative, literary work of following up on the DNA evaluation in a careful and sensitive biographical treatment. He draws on diocesan, government and tribal archives as well as the vast contemporary coverage of Williams’ life. Professional Indian is never quite a sympathetic treatment—it is hard to praise without critique someone who varies so readily among the roles of agent, spy, translator, champion, victim, pretender, servant, king, deacon, confidence man, and self-appointed spokesman for indigenous persons. Like A.J.A. Symons’s 1934 The Quest for Corvo, Oberg’s biography is as much about the process of biography when one’s subject created a multiplicity of identities for himself during various times in his life as it is a narrative account of the subject’s life. Against the backgrounds of real transnational, multilinguistic, and multiracial change—along with financial insecurity, occasional war, and governmental hostility—there is perhaps a sense in which Williams chose to fashion something implausible for the world to believe, and became caught up in believing it himself.

|

AO staff member Richard J. Mammana is the archivist of the Living Church Foundation and a member of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. He is a parishioner and vestry member at Trinity Church, New Haven, Connecticut. |