A review for Anglicans Online

by Richard Mammana

A review of

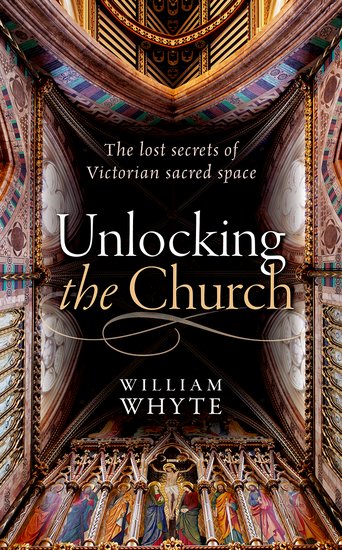

Unlocking the Church: The Lost Secrets of Victorian Sacred Space

By William Whyte

Oxford University Press, 2017. Hardcover, 241 pages. £18.99, US$24.95.

In English, the term curate’s egg refers to something “good in parts:” a dish, book, sermon or other thing one wants to say good things about, but can’t without reservation. The origin of the expression is an 1895 cartoon in the beloved magazine Punch. This new book on Victorian sacred architecture is good in parts, could be better in other parts, and might be improved with a second edition.

In English, the term curate’s egg refers to something “good in parts:” a dish, book, sermon or other thing one wants to say good things about, but can’t without reservation. The origin of the expression is an 1895 cartoon in the beloved magazine Punch. This new book on Victorian sacred architecture is good in parts, could be better in other parts, and might be improved with a second edition.

Drawing on wide reading in sermons, periodicals, and other Church literature, William Whyte of St. John’s College, Oxford looks at the revolution of architecture and church arrangement that took place in the English-speaking world in the nineteenth century. The focus is by design England-centered, with a few looks at Wales and Scotland, New Zealand and India, but there is not much attention to the spread of the same styles and groups of work in North America or Africa. (Shanghai’s cathedral and Hong Kong’s would have fleshed things out, and so would have Fredericton’s.) Taking the Cambridge Movement as its touchstone—a shorthand for the aesthetic and architectural expressions of the doctrines of the Oxford Movement, Whyte delves into the intense controversies of the middle nineteenth century over vesture, posture, gesture, incense, illumination, and the cultural meaning of changes in patterns of building by architects like Pugin, Hawksmoor, Neale, Webb, Bodley, Butterfield, G.G. Scott. Church buildings emerge as legible expressions of emphases in teaching or taste. Ought pews to be rented, or free and open? Is worship an opportunity to hear sermons and scripture mainly, or also a time to make offerings of music and non-auditory senses? In rural, urban, and academic situations, these questions consumed Anglophone Christians—Anglican, Unitarian, Presbyterian, Roman Catholic, Methodist—to points of distraction. This has been mostly forgotten (along with the multitude of societies that formed to study and work together on the topics) but we have today inherited and worship in churches shaped, built, restored, remodeled, or otherwise in some way influenced by this movement.

It is hard to know where to begin and end in wonderment at the various and obvious snags, however. In a book about churches, ought there not to be some kind of consistency about church rather than Church, about whether church dedications are possessive, about whether dedication and location are separated by a comma? Why the preponderance of misspelled proper nouns? Why in a book about visual experience are there just over two dozen low-quality illustrations in grainy black and white? (This may, of course, be a matter of production value outside of the author’s control.) Why not some attention to works like Ryan Smith’s Gothic Arches and Latin Crosses, and Phoebe Stanton’s seminal Gothic Revival in American Church Architecture, or Bremer’s brilliant 2013 Imperial Gothic: Religious Architecture and High Anglican Culture in the British Empire 1840-1870? The references to Roman Catholicism and English borrowings are also reductive: is it French, Flemish, German, Irish, Italian Catholicism, all of which have their own modes and practices?

All of these things could be sorted in a revised edition of what is still a good book with good thinking behind it. The textual bons mots are sometimes exquisite. From the index:

angels: too pretty for England

beer drinking, supposedly superseded by tea and cakes

cattle: churches used to shelter

cherubs, disappearing

cricket, an alternative to theology

evensong, linked to a rise in illegitimacy

monasticism: its revival a tricky subject for a novel

poetry, excruciating

slippers, embroidered as a tribute to preaching

tapioca, ill-advisedly used to ornament church

The prose is thus sometimes as dazzling as a chancel can be, but the stories could be packaged slightly better. The book ends on a depressing note about the closing and demolition of churches in the first world, a phenomenon that accelerates with demographic decline for most religious groups. It should be better read along with the short shelf mentioned before, as well as Pevsner, Betjeman, and Simon Jenkins’s England’s Thousand Best Churches. The resurrections of Newman’s Littlemore, Isaac Williams at Llangorwen, the sweets of Pimlico and Brian Brindley, the works of Paget and Wilberforce: all are wonderful, and they cheer a rainy winter day. And so the curate’s egg is still a good gift.

|

AO staff member Richard J. Mammana is the archivist of the Living Church Foundation and a member of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. |