Reviewed

for Anglicans Online

by R. Mammana

Lights

and Shadows

A review

of

Man

in the Middle: The Reform and Influence of Henry Benjamin Whipple, the First

Episcopal Bishop of Minnesota

By Andrew S. Brake. University Press of America. 2005.

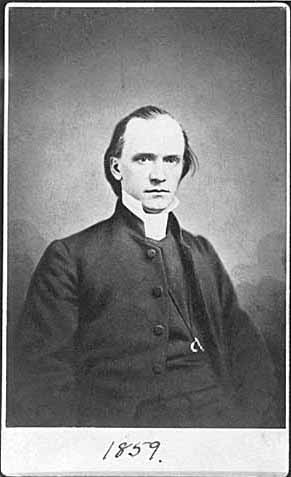

Even

in a century when now-forgotten missionary bishops of note and lasting

influence sprang up throughout the Anglican world like crocuses on a Connecticut

lawn, Henry Benjamin

Whipple (1822-1901) stands out for his lasting importance

and relative obscurity today. Whipple served parishes in New York, Florida

and Chicago before accepting election as first Bishop of Minnesota in

1859. He built the first cathedral in the Episcopal Church USA, worked

tirelessly for church extension during the 41 years of his episcopate,

and distinguished himself in his careful determination to secure fair

treatment for the rights of Native Americans on the American frontier.

Whipple's legacy of influence on Dakota and Ojibwe life continues to

be controversial. Yet his ordination of the first Native American

Episcopal priest—John Johnson Enmegabowh (1807-1902)—and his

large body of letters to elected officials

in protest against poor treatment of Indians are clear indications of

his close involvement with and concern for the lives of the first inhabitants

of his diocese. Many of the institutions he founded continue to flourish,

among them Shattuck-St. Mary's School and,

in a later incarnation, Seabury-Western

Divinity School. Yet Whipple's 1899 autobiography, Lights

and Shadows of a Long Episcopate, remains today the primary source

for readers interested in his life and work. The only sizable later biography

is Philip Osgood's brief Straight Tongue (1958).

Even

in a century when now-forgotten missionary bishops of note and lasting

influence sprang up throughout the Anglican world like crocuses on a Connecticut

lawn, Henry Benjamin

Whipple (1822-1901) stands out for his lasting importance

and relative obscurity today. Whipple served parishes in New York, Florida

and Chicago before accepting election as first Bishop of Minnesota in

1859. He built the first cathedral in the Episcopal Church USA, worked

tirelessly for church extension during the 41 years of his episcopate,

and distinguished himself in his careful determination to secure fair

treatment for the rights of Native Americans on the American frontier.

Whipple's legacy of influence on Dakota and Ojibwe life continues to

be controversial. Yet his ordination of the first Native American

Episcopal priest—John Johnson Enmegabowh (1807-1902)—and his

large body of letters to elected officials

in protest against poor treatment of Indians are clear indications of

his close involvement with and concern for the lives of the first inhabitants

of his diocese. Many of the institutions he founded continue to flourish,

among them Shattuck-St. Mary's School and,

in a later incarnation, Seabury-Western

Divinity School. Yet Whipple's 1899 autobiography, Lights

and Shadows of a Long Episcopate, remains today the primary source

for readers interested in his life and work. The only sizable later biography

is Philip Osgood's brief Straight Tongue (1958).

In

Andrew S. Brake's promisingly-titled Man in the Middle, readers

encounter Whipple primarily in the context of his efforts at reforming

the American government's Indian policy. The first three chapters provide

a biographical sketch, a helpful and interesting survey of Whipple's theology

and ecclesiology, and a look at his experiences in connection with the

Civil War. The next three chapters—'The Dakota Crisis in Minnesota

and Henry Whipple's Role in the Defense and Judgment of the Indians',

'Cultural Genocide or Survival: Henry Whipple's Work to Defend Minnesota

Indian Livelihood' and 'Legacy of Reform'—survey the bishop's work

in much the same vein as a

1901 lecture by General John Sanborn, with the difference today

being that Brake defends Whipple against charges of cultural imperialism

and genocide levelled since the 1970s by Sue Elizabeth Holbert, Martin

Zanger and George Tinker. Brake counters their criticisms by acknowledging

that Whipple was an assimilationist, but he asserts that Native American

converts to Anglicanism in frontier Minnesota had the intellectual capacity

and skill at cultural navigation 'to know when they wanted to convert

and what exactly they were doing'. In the broader context of social reform,

Brake finds Whipple to be an overlooked voice on the intellectual interpretation

of the Civil War, 'the responsibility of the wealthy toward the poor,

[on] major church issues such as unification and ecclesiology, and the

responsibility of the church toward society.' In these connections, Brake

breaks interesting new ground, but he does not situate Whipple's social

ideas within the context of his liminal place between Tractarianism and

old High Churchmanship—a border straddled notably in the United

States by contemporaries like James Lloyd Breck, Jackson Kemper, George

Washington Doane and Arthur Cleveland Coxe.

In

Andrew S. Brake's promisingly-titled Man in the Middle, readers

encounter Whipple primarily in the context of his efforts at reforming

the American government's Indian policy. The first three chapters provide

a biographical sketch, a helpful and interesting survey of Whipple's theology

and ecclesiology, and a look at his experiences in connection with the

Civil War. The next three chapters—'The Dakota Crisis in Minnesota

and Henry Whipple's Role in the Defense and Judgment of the Indians',

'Cultural Genocide or Survival: Henry Whipple's Work to Defend Minnesota

Indian Livelihood' and 'Legacy of Reform'—survey the bishop's work

in much the same vein as a

1901 lecture by General John Sanborn, with the difference today

being that Brake defends Whipple against charges of cultural imperialism

and genocide levelled since the 1970s by Sue Elizabeth Holbert, Martin

Zanger and George Tinker. Brake counters their criticisms by acknowledging

that Whipple was an assimilationist, but he asserts that Native American

converts to Anglicanism in frontier Minnesota had the intellectual capacity

and skill at cultural navigation 'to know when they wanted to convert

and what exactly they were doing'. In the broader context of social reform,

Brake finds Whipple to be an overlooked voice on the intellectual interpretation

of the Civil War, 'the responsibility of the wealthy toward the poor,

[on] major church issues such as unification and ecclesiology, and the

responsibility of the church toward society.' In these connections, Brake

breaks interesting new ground, but he does not situate Whipple's social

ideas within the context of his liminal place between Tractarianism and

old High Churchmanship—a border straddled notably in the United

States by contemporaries like James Lloyd Breck, Jackson Kemper, George

Washington Doane and Arthur Cleveland Coxe.

The closing paragraph's prose is characteristic of the book as a whole, and it illuminates the lens through which Brake has read and interpreted Whipple:

The embers of Whipple's influence and role in Gilded Age reform ought to be rekindled. It is difficult to determine why his story faded into obscurity, recovered only by those who were either Episcopal, a Whipple, or students of Indian reform. Maybe it is because his life was so interwoven with the church. Our history books unfairly crowd out the clergyman and the influence of religion too arbitrarily from the story of the American people. Maybe, then, the American story should be reconsidered in light of this Whipple and other "Whipples" who significantly impacted their worlds. In our shift to a philosophical foundation of secularization as a nation over the past century, we must be careful that we do not secularize our history as well. Perhaps the reintroduction of Henry Whipple to the field of history is a small step in the reversal of that trend.

While Man in the Middle is remarkable for its serious examination of Whipple's life and importance in nineteenth-century Anglican and American history, and for the author's deep mining of archival material, the book suffers from a general unfamiliarity with church terminology and some of the wider context in which to situate Anglican missionary contacts with indigenous peoples in North America. There is no reference to the magisterial scholarship of Owanah Anderson on Episcopal Church work among American Indians, or to missionary work by the CMS and SPG in what is now Canada, much of which was also conducted among the Ojibwe and Dakota tribes covered in this volume. On the level of biography, we never read that Whipple was invited to become Bishop of Honolulu at a time when critical choices were made with regard to that diocese's indigenous Hawai'ians and their relation to Anglo-American churches, governments and cultures. Brake refers to individuals and to Whipple himself as "an Episcopal," and to the "Archbishop of Cantebury, Rev. Dr. Longley." (In references to clergymen, Brake always uses "Rev. Gear," where "the Reverend Ezekiel Gear" or just "Gear" would be more appropriate, etc.) Run-on sentences, subject-verb disagreement and irregular capitalisation seriously mar the book's readability, and it would be wonderful to see a second edition prepared with attention to standards of normal scholarly prose. It is safe in any case to say that much more can and should be written on Whipple's fascinating life.

|

R. Mammana is an editor of Anglicans Online. His articles and reviews have appeared in Sobornost, Anglican Theological Review, The Living Church, Touchstone and The Episcopal New Yorker. |